Budhigandaki: Dam of discontent

Bhrikuti Rai / February 9, 2017

Budhigandaki River seen from Baseri village in Gorkha. Twenty-seven VDCs in Gorkha and Dhading districts will be affected by the Budhigandaki Hydropower Project. (Pics: Bhrikuti Rai)

Shyam Bahadur Thapa, 58 of Darbung VDC in Gorkha had come to the Budhigandaki Hydropower Project’s site office in Benighat on a cold December morning. The dense winter fog had lifted almost entirely by the time he hiked the dusty track ahead of the Trishuli bridge to the site office. He didn’t have to wait. The bright pink rooms in the prefab building that was opened only a few months ago didn’t have the buzz one would expect in the office of a ‘national pride project’. It took Thapa less than 15 minutes to file the application. His land registration papers, recommendation letter, and single-page application with the 10 rupee postage stamp was ready. A quick lick on the back and the stamp finalized the application.

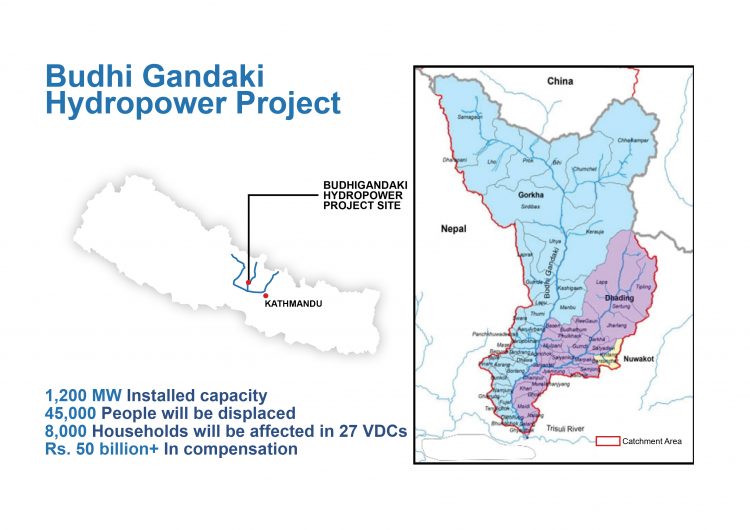

Residents of the three VDCs – Ghyalchok, Bhulmi and Darbung – of Gorkha will be among the first to receive the compensation money for the land to be acquired by Budhigandaki Hydropower Project which will have an installed capacity of 1,200 megawatt (MW). It will displace about 45,000 people from 27 VDCs of Gorkha and Dhading. According to the project development committee’s estimates, the total cost for acquiring around 58,000 ropanis [2950 hectares] of land for the project will exceed Rs 50 billion.

Compensation distribution committees in both the districts have already fixed the compensation rate – ranging from Rs 524,000 to Rs 835,000 per ropani. The land to be acquired by the project has been classified into five categories – paddy field, small farm land, land in market area, land adjoining road and land near human settlements.

Some locals from Gorkha who were dissatisfied with the compensation announcement even resorted to violent protests in December which led to several arrests after they vandalized the newly-built office in Benighat (pic,below).

Thapa is claiming compensation for 5 ropanis [1 ropani is 5476 sq ft] of land in Darbung. His house perched high on a hill will be spared by the dam that will inundate 27 VDCs in Gorkha and Dhading. Standing in front of the cracked window glass of the site office he says that people should accept the good bargain. “We can live and work the fields for a few more years or even longer depending on when the project starts,” he says. When asked about what he will do with the compensation money, he says he will buy another plot of land where he will continue farming. His brother lives in the house and farm in Darbung, while Thapa lives in the flat lands of Chitwan, some 50 kilometers from Benighat.

But there are several families who unlike Thapa don’t have anywhere ready to go once the mighty river is closed off and their homes and fields get inundated. Just a few kilometers from the dam site along the dusty tracks beside the mighty Budhigandaki is Baseri village. It lies in Gorkha’s Ghyalchok VDC and is the most affected area of the VDC with all 27 households and fields which will be inundated by the project’s dam. All the households in the village have electricity connection and water taps. Farming is the main source of livelihood for almost all the families.

Lok Narayan Shrestha and his wife who are well into their late sixties make close to Rs 200,000 annually by selling the produce from their farm. The land here is very fertile, says the elderly couple who moved to Baseri more than 30 years ago. They don’t want to be rendered homeless since they fear that the compensation they will receive won’t be enough to buy sufficient land and fields in the nearby areas of Malekhu and Benighat. Their farm land which runs alongside the road is the most prized land. They own 9 ropanis and will receive compensation of around Rs 835,000 per ropani.

Lok Narayan Shrestha of Baseri, Gorkha is worried about starting a new life in a new place after eviction.

Our house and farmlands are not just for us. “We don’t just want to have the house and farm land for ourselves; it will be for our posterity. What will we show when our grandchildren ask us where we lived and where we are from?” says Lok Narayan Shrestha.

A few meters further up from Lok Narayan’s two-story house, lives Mangal Sarki and his family of ten. He moved to Baseri almost two decades ago from the adjacent district of Dhading. “The small plot of land just wasn’t enough for us to live and farm so I moved here. Now when we have just started earning just enough to get by, we are being kicked out yet again,” says Sarki. He has close to Rs 400,000 in loan and says the money from compensation will not give them the kind of lifestyle they have here. Furthermore, he is annoyed with people who think the project-affected families are set to get tens of millions of rupees in compensation.

“It’s not that we don’t want to give away our land for development which is just as important. But all we are asking for is that they heed our demands and provide us fair compensations,” says Sarki.

As of early January none of the 27 households of Besari had filed applications to request for compensation even more than a month after the announcement. They are adamant that the entire village won’t budge unless their concerns are addressed. “If worse comes to worst we will get washed away with our homes and lands (Paanima dubera basaula),” he says with a smirk.

A few kilometers further up from Baseri across the Budhigandaki River is Majhitar village that falls in Dhading. Samsher Kumal, 55, (pictured below) sells snacks in a tiny shack on the way to Majhitar. He lives with his wife and two young sons in a mud house built in a compact three aana [1026.75 sq ft] of land. Like many in his village, he says the future is uncertain for him and his family. “People who have another house and land higher up from the village may move there, but we have nowhere to go,” he says.

Most of the Kumal households in the village don’t own huge swathes of farmland, and even the small plots that they own far from the roads aren’t all registered. Punte Kumal is among those unlucky few who neither have enough land to fetch them generous compensation nor a safe abode higher up from Majhitar that will be spared by the hydropower project. He has rented a room for Rs 1,500 per month near the adjoining dusty road where he sells snacks to the people waiting for buses. “I will not be able to buy even a small plot of land to build a house with the compensation money,” he laments, “We (Kumals from Majhitar) should all be resettled near some jungle in Chitwan because we cannot afford new land and house.”

Following the dissatisfaction of the project-affected locals, the project development committee decided to request the government to offer a ropani of residential land and Rs 1 million in cash to build a new house to each of the affected households. But people like Punte Kumal say they aren’t convinced that they will really get the compensation.

Shri Budhigandaki Primary School in Majhitar wasn’t considered for reconstruction grant.

It isn’t just the uncertain future that people are worried about here in Majhitar, their current situation is already bleak because of what is to come. Despite being in one of the most-affected districts by the devastating earthquake of 2015, Shri Budhigandaki Primary School in Majhitar wasn’t considered for reconstruction grant. Young students play around the decrepit school building with cracked walls while teachers sit under the shadow of the half-standing wall. “Since the school will submerge anyway once the hydro project construction begins, we didn’t get the funds to rebuild so have no choice but to continue classes in the temporary structures,” says Renuka Majhi, 26, who has been a teacher there for over a year. “It becomes impossible to run the classes when it rains,” she adds.

Currently, the project has round Rs 5 billion at its disposal for compensation. According to the project development committee’s estimates, the total cost for acquiring around 58,000 ropanies of land in 27 VDCs of Gorkha and Dhading will exceed Rs 50 billion.

Subhash Shrestha, a resident of Gorkha, is an engineer deployed at the site office in Benighat. He admits that the recent spat and protest did dampen the initial euphoria around the compensation process but he hopes the locals will come around and settle for what they have been offered.

“People need to understand that we cannot pay them large sums in compensation since that will make the project unviable, so we are giving them the best deal we can,” says Shrestha. After the compensation rate was fixed in November some of the locals were so furious about the rates that they threatened the project staff from visiting some VDCs for land valuation. “If only the people here cooperated, this process would have been a lot faster and smoother for everyone,” he adds.

The first to go

Barely a kilometer to the northeast from the project’s site office is the picturesque village of Kaleri nestled in the shadow of forests and above the banks of Budhigandaki. This village of 34 Magar families will be among the first to be evicted after the construction of project starts, informs engineer Shrestha.

Dil Bahadur Darlami Magar of Kaleri, Dhading stands from across his village Kaleri in Dhading which will be washed away by the project dam.

Five years ago the villagers chipped in Rs 600,000 to open a 1.5 kilometer long dirt road to connect their village to the nearest market to sell the local produce – vegetables, poultry and fish in Benighat and Malekhu. Little did they know that their return on investment wouldn’t last very long.

Dil Bahadur Darlami Magar, 47, of Kaleri says he and his fellow villagers were under the impression for a long time that their village would be spared. “At the very beginning when they started talking about the project we had heard that our village wouldn’t be affected, but now we have been told that we will be the first ones to be swept away,” says Dil Bahadur, who lives with his extended family of four brothers. Like many in his village, he says their ancestral land hasn’t yet been divided among his brothers which will make the compensation process furthermore complicated for his family.

“We had just started commercial farming but all of this will be gone soon,” he laments. He says his produce fetched him Rs 400,000 to 500,000 annually which was enough to raise his family. Like his neighbors, he is worried that the inundation of his home and village will bring them to the streets. “What we will receive as compensation will not be enough for us to start a new life from scratch, we’ll be beggars,” he says.

This material is copyrighted but may be used for any purpose by giving due credit to southasiacheck.org.

Comments

Latest Stories

- In Public Interest Covid-19 cases are low, but that’s not an excuse to avoid vaccination

- In Public Interest What is BF.7, the sub-variant that has the world by its grip?

- In Public Interest Threat of a new Covid-19 wave looms large amid vaccine shortage in Nepal

- In Public Interest As cases decline, Covid-19 test centres in Kathmandu are desolate lot

- In Public Interest Dengue test fee disparity has patients wondering if they’re being cheated

- In Public Interest As dengue rages on, confusion galore about what it is and what its symptoms are. Here’s what you need to know

In Public Interest

Covid-19 cases are low, but that’s not an excuse to avoid vaccination

The Pfizer-BioNTech bivalent vaccines authorised by the Nepal Government provide better protection a...

Read More

Covid-19 cases are low, but that’s not an excuse to avoid vaccination

The Pfizer-BioNTech bivalent vaccines authorised by the Nepal Government provide better protection a...

Read More

- What is BF.7, the sub-variant that has the world by its grip?

- Threat of a new Covid-19 wave looms large amid vaccine shortage in Nepal

- As cases decline, Covid-19 test centres in Kathmandu are desolate lot

- Dengue test fee disparity has patients wondering if they’re being cheated

- As dengue rages on, confusion galore about what it is and what its symptoms are. Here’s what you need to know