What kept the Madhes agitation from taking a communal turn?

Sujit Mainali / February 20, 2016

The Ghantaghar Chowk in Birgunj strewn with stones after a clash between police and Madhesi protestors in this December 2015 photo. Photo: Sujit Mainali

“The risk of communal violence between pahadis and Madhesis is real. The line between the struggle against the state and against pahadis has blurred in Madhesi politics; armed groups have selectively targeted pahadi bureaucrats and businessmen; pahadis have become insecure, and some are migrating.”

The report published by the International Crisis Group immediately after the first Madhes uprising had noticed the risk of communal violence in Madhes.

This time, the agitation in Madhes continued for over five months. The agitation deeply influenced the people of even far-flung corners of the Tarai. But communal harmony remained undisturbed. It is believed that the maturity of the people of Madhes, rational and judicious orientation given to the cadres and protestors by their leaders, regular interaction between the local administration and the movement leaders to prevent the situation from taking a communal turn, and the solidarity expressed by the hill-origin people of Madhes with the agitation, among other things, prevented the situation from getting out of hand.

After the Kailali incident that occurred in late August, Madhes movement gained momentum in province number 2, where Madhesi people are in a majority. After the agitation intensified, people from far flung villages of the Tarai also began to actively participate in the movement and also started sit-ins at Nepal-India customs points.

After the people of Madhes were repeatedly told by their local leaders that the leaders in Kathmandu have deprived the Madhesi people of their rights, the Madhesi people started to feel that the struggle was justified. As more people started dying from police bullets in Madhes in the aftermath of the Kailali incident, Madhesi people became enraged and they started defying curfew orders and more joined the sit-ins at border points to stop supplies to Kathmandu.

“I joined protests although I knew that police shoot protestors directly in the chest. I was not afraid of death. I was prepared to face death any moment,” Shiva Devi Patel, a farmer from the Chaukiya Bairiya village of Parsa district, told South Asia Check.

When the agitators attempted to vandalize the police post at Nagwa in Birgunj, police opened fire to disperse the agitators. Patel was also among the protestors.

“When the firing started, there was a stampede. But I stood without moving, ready to receive bullet in the chest,” he said.

Shiva Devi Patel, a farmer from the Chaukiya Bairiya village of Parsa. Photo: Sujit Mainali

One protestor died in that incident. About 25-30 people including policemen were injured. Luckily, no bullets hit Patel but he received a minor injury in the leg when a pebble hit him.

Patel also participated in the joint cremation of five protestors on the bank of the Tilawe River. The five were killed before and after the Nagwa incident. “It galled me when I saw that the people fighting for their rights were being shot. For one moment, I was so enraged that I wanted to kill someone,” he said.

When asked whom he wanted to kill and if it was someone from the hill community, he replied, “The people of hill community have not done us any harm. I wanted to kill the leaders whom I had elected.”

Asked if the local politicians had told them not to target the people from the hill community, he said, “No. I learnt it on my own. Politicians do not tell good things, they rather spoil things.”

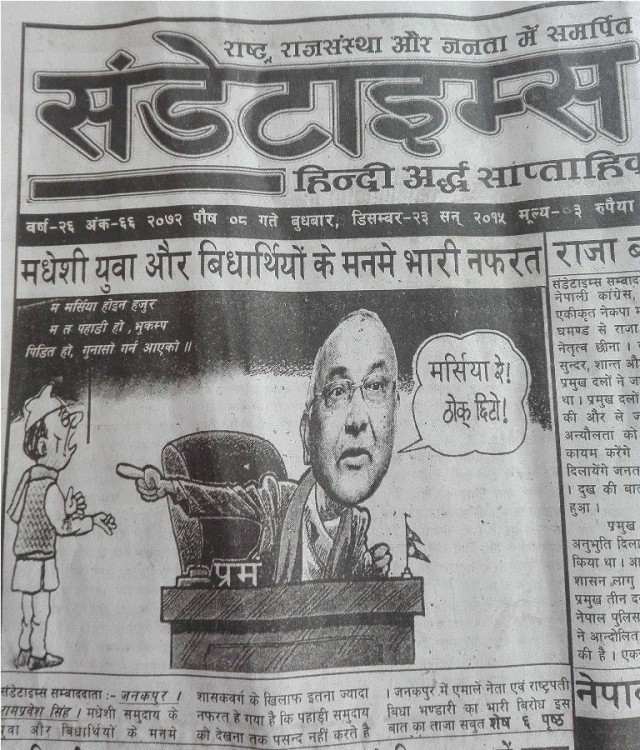

On December 23, the front page main story of the Sunday Times, a Hindi biweekly newspaper published from Birgunj, stated, “Madhesi youths and students hate the ruling elite so much that they don’t even want to see the face of the people from the hill community anymore.” But Patel’s statement and the fact that there was no report of any clash between the Madhesi and the people of the hill community during the protracted agitation, falsified the assertion of the Sunday Times.

December 23 edition of Hindi biweekly Sunday Times published from Birgunj. Photo: Sujit Mainali

Agitation not targeted against any community

All the protestors who were contacted during the agitation said the same thing: “Our movement is not against any particular community. It is against the discriminatory state.” Local leaders who addressed the mass meetings during the agitation were also found repeating this statement.

Pramod Tiwari, a resource person at the District Education Office, Parsa, said, “Also due to such mature and rational political orientation by movement leaders, the Madhes movement did not take a communal turn and did not lose its political character.”

When the agitation was ongoing, in mid-December, Pradip Yadav, the district (Parsa) chairman of the agitating Federal Socialist Forum Nepal had told South Asia Check, “This movement belongs to all the oppressed communities of Nepal. The oppressed communities of the hills are also with us. As this movement is for finding solution to the common problems faced by both the Madhes and the hills, it will not take a communal turn.”

To substantiate his argument, he recalled that the chairman of his party, Upendra Yadav, had addressed the mass gathering of the supporters of Tamuwan and Magaraat in Pokhara two days ago [December 14].

“This agitation will not divide the hills and the Madhes. Instead, it will unite them,” Upendra had said.

However, communal harmony during the agitation was not at their best. According to the chief district officer (CDO) of Parsa, Keshav Raj Ghimire, when the agitation was at its peak, communal tolerance was on the brink of collapse.

When the protests were at their peak, 20-25 thousand protestors armed with domestic weapons and guns would come to Birgunj to defy the curfew and to encircle police stations. “We had even deployed the army after sensing that the strength of Nepal Police and Armed Police Force alone would be insufficient for dealing with the situation,” he said.

According to CDO Ghimire, the administration had assessed that communal tolerance was at higher risk. “But in the meantime, people of the hill community staged a march expressing solidarity with the Madhes movement and this prevented the situation from getting out of control,” he said.

The people of hill origin living in Mahottari, Saptari, Sarlahi and some other districts of the Tarai also organized rallies in support of the movement.

Prakash Kumar Upadhyay (Bhattarai), a member of hill community currently residing in Birgunj and who is also a former Mahasamiti member of the Nepali Congress (NC), opined that other communities expressed solidarity with the movement as the demands of the movement were political in nature.

“The movement has demanded an inclusive constitution. Nepali society is mixed, so this demand seems rational enough, and the people of the hill-origin in Tarai supported the movement. We, from the local level, exerted pressure on the party [Nepali Congress] to formally express solidarity with the movement,” he said.

According to CDO Ghimire, the local administration was in regular touch with the agitating parties to prevent the movement from taking a communal turn.

“The leaders of the movement were also aware that the movement should not take a communal turn. They were equally worried about the movement losing its very essence in the event of communal discord,” he said.

Ghimire said the state had exercised enough caution to prevent communal discord.

He said he had asked the higher-ups to deploy more security personnel of Madhesi origin in the Tarai if possible but not reduce their existing numbers, so as to maintain communal balance.

“For holding dialogue with the agitators, we used to send teams comprising security personnel from both the hill and Madhes origins. This enabled us to bridge the language barrier as well. Also, we cautioned security personnel not to use abusive words against the protestors which could hurt their sentiments. Assuming that deploying same security personnel at the same place for a long time may annoy them and personal enmity may develop between such security personnel and protestors, we used to rotate them at different locations,” he said.

According to resource person of Parsa, Pramod Tiwari, the leaders, protestors and common people of Madhes were wary of the possibility of a backlash if communal violence erupted in Madhes.

“They were mindful of the possibility that if communal violence started in Tarai, it would set off a chain of violence across the country. And in that event, whole communities of Nepal including Madhesis living in Kathmandu and other hilly areas would have to bear the consequences,” he said.

According to Tiwari, when observed from outside, it seemed that the Madhes agitation strengthened the possibility of secession and communal violence, but that was not the fact on the ground. “You talk to anyone on the street, and they will say they want delineation not secession. If you ask them whom is the agitation aimed at, their reply would be the government and not the people of hill origin,” he said.

References:

- Nepal’s Troubled Tarai Region, July 8, 2007, International Crisis Group

- Republica Daily, Nepal Republic Media

- The Kathmandu Post, Kantipur Publications

- Interview with the stakeholders and field observation

This material is copyrighted but may be used for any purpose by giving due credit to southasiacheck.org.

Comments

Latest Stories

- In Public Interest Covid-19 cases are low, but that’s not an excuse to avoid vaccination

- In Public Interest What is BF.7, the sub-variant that has the world by its grip?

- In Public Interest Threat of a new Covid-19 wave looms large amid vaccine shortage in Nepal

- In Public Interest As cases decline, Covid-19 test centres in Kathmandu are desolate lot

- In Public Interest Dengue test fee disparity has patients wondering if they’re being cheated

- In Public Interest As dengue rages on, confusion galore about what it is and what its symptoms are. Here’s what you need to know

In Public Interest

Covid-19 cases are low, but that’s not an excuse to avoid vaccination

The Pfizer-BioNTech bivalent vaccines authorised by the Nepal Government provide better protection a...

Read More

Covid-19 cases are low, but that’s not an excuse to avoid vaccination

The Pfizer-BioNTech bivalent vaccines authorised by the Nepal Government provide better protection a...

Read More

- What is BF.7, the sub-variant that has the world by its grip?

- Threat of a new Covid-19 wave looms large amid vaccine shortage in Nepal

- As cases decline, Covid-19 test centres in Kathmandu are desolate lot

- Dengue test fee disparity has patients wondering if they’re being cheated

- As dengue rages on, confusion galore about what it is and what its symptoms are. Here’s what you need to know