Pesticides tests of fruits and vegetables, problems galore

Injina Panthi / July 13, 2018

Vegetables at the Kalimati Fruits and Vegetables Market, at Kalimati, Kathmandu. Photo: Injina Panthi

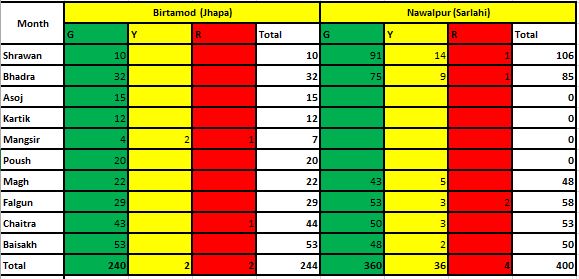

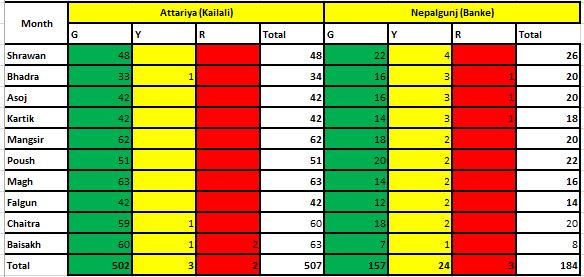

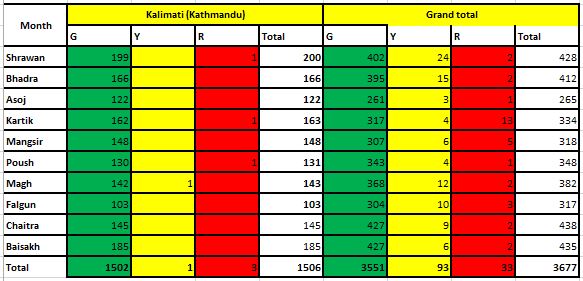

Pesticides residue tests of fruits and vegetables conducted by the government in various parts of the country between July 16, 2017 and May 14, 2018 have revealed that out of 3,677 samples 33 were found inedible due to high concentrations of pesticides. Likewise 93 samples of fruits and vegetables were quarantined. In most cases, the quarantined samples can be consumed after a few days.

Tests results between Shrawan 1, 2074 (July 16, 2017) and Baishakh 31, 2075 (May 14, 2018)

Note: In the tables, green signifies edible, yellow quarantined and red means inedible.

Note: Nawalpur test lab conducted pesticides residue tests for six months only owing to floods and power outages.

Source: Plant Protection Directorate

Among the seven pesticides residue test labs across the country, the lab in Pokhara of Kaski district recorded the highest numbers of inedible fruits and vegetables samples during the period. Out of the 507 samples tested at the Pokhara lab, 19 were inedible while 23 samples were quarantined.

Likewise, out of 400 samples tested during the period by the lab at Nawalpur of Sarlahi district, only four samples were found unsafe for consumption and 36 samples needed quarantine.

The Nepalgunj lab had tested 184 samples during the period and only three were found inedible while 24 samples were quarantined. Similarly, out of the 1,506 samples tested by the Kathmandu-based Kalimati lab, three were found highly toxic and one was quarantined. The Birtamod lab in Jhapa tested 244 samples and two were found inedible while two samples were quarantined.

At the Butwal test lab no fruits and vegetables were found inedible during the 10 months. Out of the 329 samples tested only four samples were quarantined.

The vegetable items that failed the pesticide residue test at Kalimati lab included snake beans [tane bodi], chili and okra. These vegetables were supplied from Dhading, Makawanpur, and Sarlahi districts.

At the Birtamod lab, tomato and banana from India and Ilam had failed the pesticides residue tests.

In Nawalpur, the test lab conducted pesticides residue tests for six months only. The lab said tests could not be conducted for four months – from mid-September 2017 to mid-January 2018 – due to floods and power outages. Out of the 400 samples tested during the six months four were inedible. The contaminated vegetables and fruits were brought from Mohattari and Sarlahi. One bean sample, two samples of cowpea and one tomato sample were found containing high concentrations of pesticides residue.

At the Pokhara pesticides residue test lab, vegetables and fruits from Kaski, Rupandehi, Sarlahi, Syangja, Tanahun, and India were found containing high levels of pesticides. Three bean samples, four potato samples, one tomato sample and one zucchini sample were found inedible. Likewise, nine orange samples and one junar [a variety of sweet orange] sample were found inedible.

At the Attariya lab in Kailali, cucumber and okra brought from Kanchanpur were found containing pesticides in high amounts.

The Rapid Pesticide Residue Analysis Laboratory at Kalimati was started in June 2014, and the other six labs had come in operation from April 2017.

According to Ramkrishna Subedi, information officer at the Plant Protection Directorate, “The testing of vegetables and fruits for pesticides residue is in preliminary stages in Nepal and there are several challenges.” He further stressed the need for better coordination between the Ministry of Agriculture/Plant Protection Directorate, Ministry of Home Affairs/police, and the district administrations for making the tests more effective. At present, the Ministry of Home Affairs has not shown any interest in the issue. Ideally, the fruits and vegetables lots which are being tested for pesticides residue should not be sold until the lab report is released, but this has not been happening and even inedible fruits and vegetables reach the kitchen before the lab report comes in. Since the sale is not suspended until the release of the lab test report, fruits and vegetable vendors do not take the tests seriously.

Testing chemicals are not available in the local market

The rapid bioassay of pesticides residues (RBPR) technology being used in Nepal was developed in Taiwan. The chemicals needed for the tests are not available in the local market so they have to be imported through private suppliers. The current technology in use in Nepal only tests the toxicity of organophosphate and carbamate chemicals. “Initially, we would test ten samples, but over the past few months, we have been testing around six samples per day due to shortage of testing chemicals, which are costly,” said chief officer Man Bahadur Chhetri of the Kalimati lab.

The major reason for adopting RBPR is that organophosphates-based pesticides are widely used in Nepal. “Until a few years ago, around 80 percent of the pesticides used in Nepal would be organophosphates-based. This has come down to around 60 percent over the past two years,” said Subedi.

Although preparations are under way to bring equipment to test the chemicals used to kill sensitive parasites and fungi, there is no plan to bring the technology to test several other pesticides residues.

Manpower shortage

The Plants Protection Directorate had asked the government to provide four staffers per lab but, the government approved only two temporary staffers per lab. Currently, the Attariya lab is manned by two staffers, Nepalgunj lab by one staffer, Butwal by two, and Sarlahi lab is being manned by just one staffer. Although there are two staffers at the Birtamod lab, one of them is currently working for the Agricultural Development Office and the municipality, so the lab is manned by just one staffer. At the Pokhara lab, one of the staffers recently retired and the other was transferred elsewhere, so the lab is currently being manned by a staffer deputed from the Agriculture Development Office. Lack of human resources and multiple engagements of deployed staffers have been affecting the testing process.

Information officer Subedi points to the need for setting up pesticides testing labs at the entry/exit points of the fruits and vegetable farming pocket areas. In Nepal there are about 300 such pocket areas, and if two testing labs are set up per pocket area, then excessive use of pesticides will stop, according to Subedi.

But on the other hand, in some places of Kavrepalanchowk, Chitwan, Tanahun, Jhapa, Banke, Kailali and Kapilbastu districts, vegetables and fruits are being produced using biological pesticides. But the market for such produces has yet to grow.

This material is copyrighted but may be used for any purpose by giving due credit to southasiacheck.org.

Comments

Latest Stories

- In Public Interest Covid-19 cases are low, but that’s not an excuse to avoid vaccination

- In Public Interest What is BF.7, the sub-variant that has the world by its grip?

- In Public Interest Threat of a new Covid-19 wave looms large amid vaccine shortage in Nepal

- In Public Interest As cases decline, Covid-19 test centres in Kathmandu are desolate lot

- In Public Interest Dengue test fee disparity has patients wondering if they’re being cheated

- In Public Interest As dengue rages on, confusion galore about what it is and what its symptoms are. Here’s what you need to know

In Public Interest

Covid-19 cases are low, but that’s not an excuse to avoid vaccination

The Pfizer-BioNTech bivalent vaccines authorised by the Nepal Government provide better protection a...

Read More

Covid-19 cases are low, but that’s not an excuse to avoid vaccination

The Pfizer-BioNTech bivalent vaccines authorised by the Nepal Government provide better protection a...

Read More

- What is BF.7, the sub-variant that has the world by its grip?

- Threat of a new Covid-19 wave looms large amid vaccine shortage in Nepal

- As cases decline, Covid-19 test centres in Kathmandu are desolate lot

- Dengue test fee disparity has patients wondering if they’re being cheated

- As dengue rages on, confusion galore about what it is and what its symptoms are. Here’s what you need to know